Silent Recasting Blogathon: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1917 – a 17-Chapter Serial by Louis Feuillade)

This is my contribution to the Silent Recasting Blogathon at Carole and Co.

Had I given this post more time, in terms of design, I’d have come up with an actual one sheet as opposed to just a color-corrected banner image. However, what I am lacking in graphics I am prepared to try and make up for in terms of an alternate history narrative.

In this take I am imagining a parallel universe wherein there is a J.K. Rowling who instead of publishing Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in 1997 did so in 1897. With the book being published at this time, I also imagine that the British title would not have been changed for US audiences, due to the fact that American English and the King’s English were more closely related at the time.

What I imagine would have ensued had such a book come into being 100 years before it actually was written is quite a long process wherein the rights to the cinematic adaptation of the book changed hands a few times, and eventually taking 20 years to bring to the screen.

In fact, in this alternate history all the books would’ve been published, and similarly successful, before any film version had been made.

The development of the motion picture first started under the auspices of Georges Méliès and Star Film Company. However, with the closest thing to extended narrative that Méliès had offered where things like series of shorts based on The Dreyfus Affair and titles roundabout 30 minutes he felt uncomfortable fully committing to adapting the title to the big screen. As Star fell on hard times he let his option lapse prior to his first dealings with Gaumont in 1910.

When the rights were free again British filmmakers were again outbid. This time by Ufa in Germany. They tinkered with the idea for a few years and were willing to give a young, as of yet unproven, Fritz Lang a go at it and even began the casting process a few times, but ultimately they were not yet ready to take the project on properly.

Gaumont then finally got their chance at the rights in 1916. They began discussing the project with Louis Feuillade. Feuillade at this point with both Fantomas and Les Vampires under his belt had some clout and wanted to treat the book faithfully and turn the 17 chapters in the book into 17 shorts making one serialized feature. Though they were already casting the budget required to shoot that much material of so fantastical a story became something that Gaumont would ultimately balk at.

It was clear that it was a monumental task for any one studio to take on a globally renowned tale in an age when the concept of a worldwide blockbuster did not yet exist. Untrod trails were being blazed and nervousness abounded.

That was when Carl Laemmle and Universal Studios stepped up to the plate and offered a co-production deal that would not only guarantee many screens in the US but also assistance on inter-titling the film in quite a few language that would likely lead to the films profitability.

With Universal shouldering much of the financial burden they were able to make a few demands: first, production would move to Hollywood. They would willingly retain Feuillade and have him work with a translator, but would need to discuss new casting options.

With such a big, unprecedented project underway studio affiliations were all but meaningless and the stars lined up. Eventually, the cast started to come together with many of Feuillade’s original choices being replaced by American counterparts.

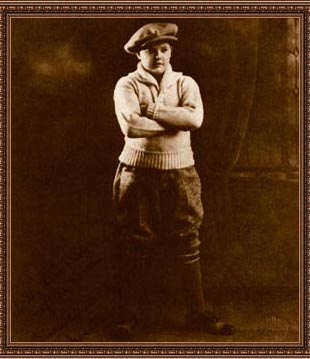

In the role of Harry, Gordon Griffith was cast replacing Fabien Haziza whom Feuillade had directed in Judex.

Feuillade didn’t have a Ron, so he was open to discussions. It ended up being one of the more heated debates. Wesley Barry was considered as he was actually a ginger. However, Laemmle argued, especially in black-and-white and tinted film, that that didn’t matter so the role ended up going to the more expressive Coy Watson, Jr.

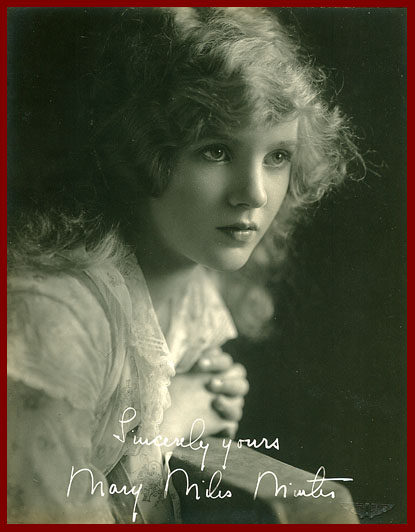

Hermione was the role most bantered about. As opposed to the boys, few of the actresses considered were actually the age they were playing. Due to that fact much crystal-ball-gazing was done as they debated who would be able to play Hermione as the series progressed with the least likelihood of needing to be recast. Eventually hopes for longevity won out over bigger name older actresses and Mary Miles Minter, got the part and eventually lead to her also being cast in Anne of Green Gables.

Many of the supporting parts were open-and-shut discussions.

Harry’s friend Neville Longbottom was a role they were unafraid to go overseas for and cast Tibi Lubinsky (a.k.a Tibor Lubinszky, seen in the center of the photo below).

While Draco Malfoy, another nemesis, was cast locally with True Boardman, Jr.

The Dursleys were decided quickly. Buddy Messinger was selected as Dudley and Louise Fazenda and Mack Swain, who had paired so often in the Wilful Ambrose films, would bring the necessary comedy to his parents.

John Barrymore, carried himself with a gravitas beyond his years, and was cast as Albus Dumbledore.

On the comeback trail, and with the film in need of more comedic touches (as per the studio not necessarily per Feuillade), Fatty Arbuckle was cast as Hagrid.

The overly-nervous Professor Quirrel was deemed to be a job for Harold Lloyd.

While, his superior, and villain to the whole series could only be the Man with a Thousand Faces, Lon Chaney.

The role of Severus Snape was one much debated as Feuillade wanted something to stem the tide of comedic actors coming in to preserve some balance at least. The final two candidates were comedian Max Linder and as-of-yet-unknown German actor Mac Schreck. Feuillade won the argument and Schreck’s appearance in this film would make waves in Germany especially with F.W. Murnau who would later cast him in Nosferatu.

As opposed to the Harry Potter series in actuality, which had to replace Professor Dumbledore (Michael Gambon took over after Richard Harris’ death), here it was Minerva McGonnigall that needed to find a new actress to fill the role later on. Sarah Bernhardt who would start the series and was unable to complete it. Feuillade was able to convince Universal that the inclusion of the renowned French stage actress would add box-office appeal among women.

With such a cast as this in place this alternate-universe version of the film was a hit akin to the one in our own. As for who would come in to play key figures down the line that may be decided in future blogathons, or can be speculated in the comments below. Hope you enjoyed!