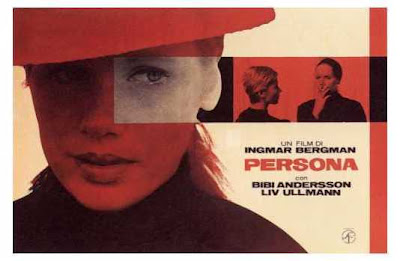

“…And scene!” Blogathon: Persona (1966) The Repeated Scene

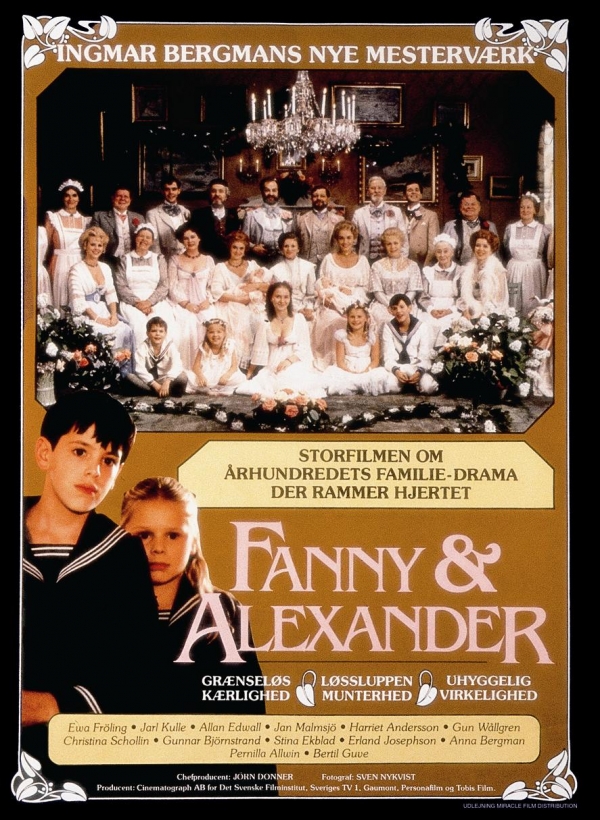

Introduction: Fanny, Alexander and the Magic Lantern

When dealing with a film that Bergman chronicles as being highly personal I feel it is only right that I give it the same treatment when I discuss it here.

There are times when I cannot help but inextricably tie my discovery of a filmmaker, or the genesis of my admiration for them, to the strength of my connection to their work. Which is to say Hitchcock and Bergman, for example, whom I gravitated to without prodding, and of my own volition, hold a more special place in my heart and mind than directors whose greatness I recognize but only found their work after hearing tell of how worthwhile an investment of my time it was and very consciously decided to watch them.

Specifically regarding Bergman, the story of my first viewing is that I decided to take the plunge when I was visiting family in Brazil. I saw a region 0 DVD of Fanny and Alexander on sale and even though to be able to see it I’d really do two translations (hearing Swedish audio, reading Portuguese subtitles and transposing it to English mentally); I went for it anyway.

I almost instantly loved the film a great deal and it fast became one of my favorites. I then proceeded to watch whatever Bergman I could from my teenage years through the present. DVDs were upgraded to Blu-rays at times; new-to-me titles acquired blind; repertory screenings at the Film Forum taken in when I was lucky enough to see them; his swan song was viewed the weekend it was released, dominating much of my annual BAM Awards; and then with his passing an honorary award with his name was created, and has a backstory of its own.

Fanny and Alexander (which I also got the box-set for and then viewed all versions, loving the TV version more than the original) was the impetus not only for my admiration but the best example of how I always inherently, nearly by osmosis, attributed to his films the axiom that the emotional truth of them was far more significant than the literal truth of the nearly fictitious “one true, correct meaning.” For it was without noticing really that I virtually never considered the wild conundrum, the paradox really, that exists in the telling of Fanny and Alexander until I revisited it and saw alternate versions.

Thus, when I made it around to Persona, which I believe I first saw as a VHS rental before getting a DVD, it was one I instantly knew I wanted to come back and dissect. Even though I got the Repeated Scene, and it may not even be my favorite part of the film, I always came back to it.

When I began my journey with Bergman, much like Alexander watching the images produced by the magic lantern, I was transfixed, as if by a wholly new experience unlike any I’d seen. Through Bergman’s eye the Repeated Scene in Persona was perhaps the most hypnotically dazzling. So here goes …

The Scene

For those who have seen the film but would like a refresher here is a YouTube link that works (for now) Those who have not seen it are advised to read carefully and selectively and see it as soon as they can:

The Text

Stepping back from the audiovisual image to the script we can look at a few different things.

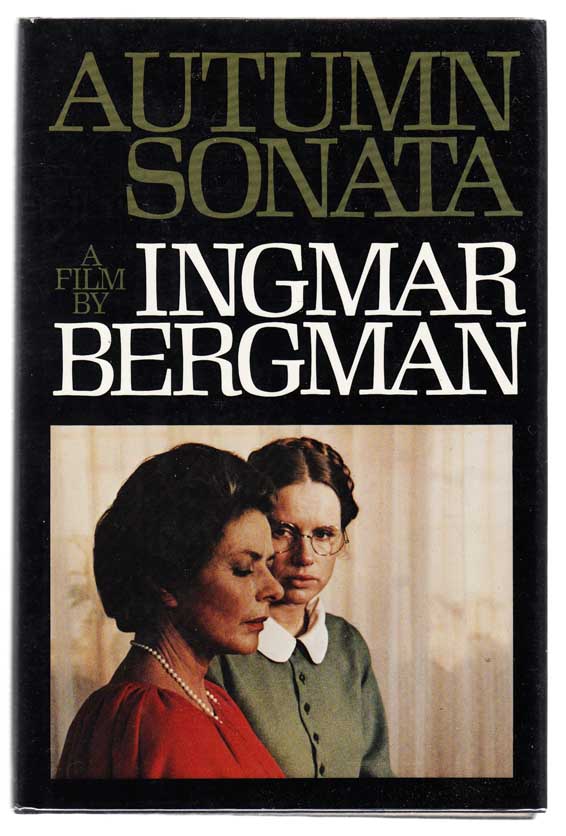

My need to be current on Bergman has extended a bit beyond films. Be they plays, screenplays, even his novels, I’ve read quite a bit of his work also. Some I took out from the library or photocopied, some I felt impelled to get like the recently republished Persona and Shame screenplays in a single volume.

A few things that become readily apparent when reading the screenplays are:

- The edit is the final process so certain things are altered or augmented by the editing process. Specific to Persona the doubling, the very repetition of the scene, was a construct of the editing room rather than the initial design. It doesn’t make it any less a calculated decision just one that came to the film when it was deemed necessary. It’s the same reason famed editor Walter Murch would line up stills of the first frame of each scene in grids, not just to get a different look at the project as a whole (in abstract), but it also provided the occasional new idea.

- As for the text itself, it’s instigated by an action and it gains added weight and significance by the visual treatment of the scene. For as talky as Bergman can appear and be he worked in theatre sufficiently to know very well the delineation and the framing, lighting, and editing were always pivotal as well as the dialogue painting images where the camera could not.

Bergman’s thoughts on the dialogue itself as well as the genesis for his creation of the film will be covered in the next section. What matters here are the basics:

An actress Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) at the height of her fame and power consciously stops speaking but is just short of a breakdown and nothing is deemed physically or psychologically wrong with her. She and her nurse, Alma (Bibi Andersson), retreat to a country estate while she recovers. As Alma talks to her and observes her they clearly make an impression on one another such that the line that separates one from the other is blurred.

Also interesting to note, is that this film had a change of shooting locale from Stockholm to Fårö Island that remedied many of the issues Bergman and company perceived when they saw the need for reshoots.

In examining the photo of Elisabet’s son that was Alma concocts a story about who this child in the ripped up photograph is clearly her son, so why is it ripped up? Alma speculates, to put it bluntly and concisely, that he was: the abortion that never happened. However, after the seeming coup de grâce of this judgment Alma reaffirms that she is she and coming up with something. She isn’t Elisabet only she can be.

Then the cycle starts anew. Alma repeats the story from a different point-of-view, in the camera’s view. However, where the tale was not quite complete here it is with Alma struggling against Elisabet invading her mind and soul. The story becomes Elisabet’s and Elisabet becomes Alma.

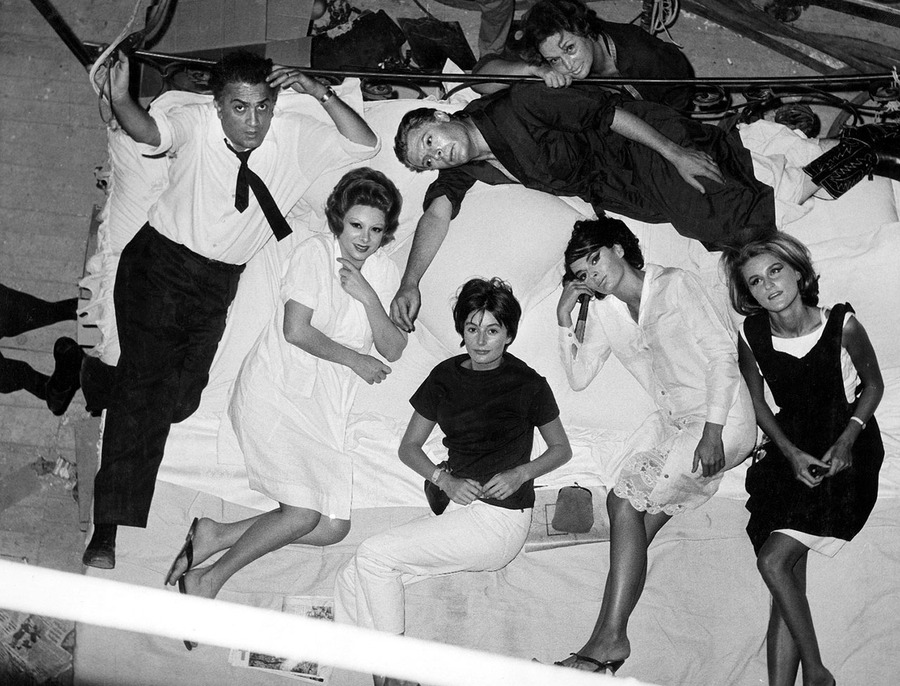

The first half of the sequence culminates in the (in)famous double-image of the “bad” side of each of their faces spliced together in one frame.

The transformation is not as literal as it would be in a genre film but for the intents and purposes of this story its just as true and for either character to move on whether recovered or depleted a fracturing needs to occur to get them apart from one another.

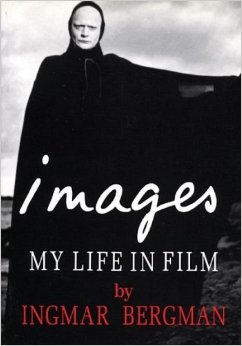

Ingmar Bergman’s Perspective in Images: My Life in Film (1995)

Many directors bristle at symbolism being imposed on their work or film theorists. And, at times, the bristling is more about that old chestnut of the “one, true version.” When it is quite clear that certain directors like Kubrick invited audiences engaging and refused to define the film for its audience. Therefore, Bergman’s background he gives on the making of the film give you the genesis, what was happening with him and how it shaped him and the story.

It should be noted that right before this he was burning the candle at both ends frequently writing and directing films for Svensk Filmindustri and was then appointed director of the Royal Dramatic Theatre. It was a lot but he thought he could handle it and ultimately chalked it up as so: “That experience was like a blowtorch, forcing a kind of accelerated ripening and maturing.”

After writing, shooting and promoting All These Women, and directing Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler for the stage, his health was waning: fever lead to double pneumonia and acute penicillin poisoning. As he was admitted to Sophiasammet Royal Hospital to recuperate the idea for Persona struck him and he began to work on it “mainly to keep my hand in the creative process.” And in doing so it was a bit freeing in a few different ways.

With an unmade project canceled, his wondering about the place of theatre in the art world, and himself as an artist; he found a vehicle to express these doubts and pains and channeled it mostly through Elisabet Vogler’s personage. This is an emotional state he accurately encapsulated in what he wrote when he accepted the Dutch Erasmus Prize, an essay entitled “The Snakeskin,” which served as the foreword for the published edition of Persona. That state is rounded out and linked to the film more thoroughly in the book.

What is perhaps most fascinating is that I had not read this book, whole or in part before researching this (only the “Snakeskin” portion in Persona); so there was much information to discover, and it’s always interesting to glean insights into an artist’s creative process, but more illuminating that that is the fact that much of this story and truth is translated to the screen without overt underlining. It’s there, you feel it, and it either affects you or it does not but it’s there for you to see. Bergman’s art is not unlike his philosophy on why he is an artist:

“This, and only this, is my truth. I don’t ask that it be true for anybody else, and as solace for eternity it’s obviously rather slim pickings, but as a foundation for artistic activity for a few more years it is in fact enough, at least for me.”

In his notes Bergman has not only poetics about his creative crisis and things that are implied by the film like “The conception of time is suspended,” and most importantly “Something simply happens without anyone asking how it happens.” Yet there is also the key to the emotional heart of the film, which is right there in the film itself:

Then I felt every inflection of my voice, every word in my mouth, was a lie, a play whose sole purpose was to cover the emptiness and boredom. There was only one way I could avoid a state of despair and a breakdown. To be silent. And to reach behind the silence for clarity or at least to try to collect resources that might still be available to me.

Here, in the diary of Mrs. Vogler, lies the foundation of Persona.

It’s interesting to note here that Bergman, as he himself notes has named a character Vogler before such as in “The Magician —with another silent Vogler in the center — is a playful approach to the question.” The name would then pop up in later films. The usage of silence, one of the quintessential traits of cinema that separates it from the stage, is also strongly present in this title as well as others by Bergman including the appropriately titles The Silence which features hardly any spoken dialogue.

About the Repeated Scene specifically he writes in his book:

“…Suddenly they exchange personalities.”

“They sit across from each other, they speak to each other with inflections of voice and gestures, they insult, they torment, they hurt one another, they laugh and play. It is a mirror scene.

The confrontation is a monologue that has been doubled. The monologue comes, so to speak, from two directions, first from Elisabet Vogler, then from Alma.”“We then agreed to keep half their faces in complete darkness — there wouldn’t even be any leveling light.”

Leveling light here refers to fill light, which is any light that would be aimed at the darker side of an actor’s face to lessen the contrast ratio. In keeping the highlight normal and the fill side very underexposed there is an inherent additional disquiet added to the viewership of the scene combine that with the editing tactics, then the unconventional treatment of the dual dialogue, including some jump cuts, and there is a crescendo to climax that is fairly universal even if the beats are more subsumed and the conflicts more internalized than in a standard, conventionally structured and told film. Upon seeing rushes of the scene edited Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann reacted as follows:

Bibi exclaims in surprise: “But Liv, you look so strange!” And Liv says: “No, it’s you, Bibi, you look very strange!” Spontaneously they denied their own less-than-good facial half.

The trick had worked and fooled the actresses themselves into seeing each other’s faces on the film. The film from that point was already speaking to people through its images alone. Yet despite the unconventional approaches, even on the written page, Bergman warns about those as well saying that “The screenplay for Persona does not look like a regular scenario.” And that it “May look like an improvisation,” but it is quite clear that there is a meticulous level of plotting that is only elevated by the inspired choice made in the edit.

Even though Bergman saw his return to his position at the theatre as a temporary setback (“When I returned to the Royal Dramatic Theatre in the fall, it was like going back to the slave galley.”) there is no doubt that Persona was a personal triumph due to the very personal, even if abstracted, look at himself that revitalized virtually everything in his life as evidenced by the statement “I said that Persona saved my life — that is no exaggeration.” Persona also marked an artistic revolution for Bergman, a change in his whole approach wherein he realized “The gospel according to which one must be comprehensible at all costs, one that had been dinned into me ever since I worked as the lowliest manuscript slave at Svensk Filmidustri, could finally go to hell (which is where it belongs!).”

Liv Ullmann’s perspective in Liv Ullmann: Interviews (2006)

What Ullmann added in interviews through the years does speak more to the scene itself, and as one of its participants she gives tremendous insight into the making of it, as well as her process as an actress. Also, how she was cast became a legendary story as she is a Norwegian-born actress and Bergman had only worked with Swedish actors at the time. It is the kind of stuff legends are made of but not as fantastical as people make it out to be.

“He had seen one picture I’d been in. And it wasn’t like he picked me up off the street, because I’d been an actress for many years in Norway. But he did take a terrible chance because I was very young — I was twenty-five — and I was to play a woman at the height of her career and having neurosis, which I knew nothing about. So he decided to use me on intuition, and I did the whole part completely by intuition, because I only understood what it was about many years later.”

About production specifically:

“That was very strange because he did that with two cameras. There was one on Bibi when she told my story. It was supposed to be cut up, using the best from each. But when he saw it as a whole, he didn’t know what to pick. So we used them both. Many people have tried to analyze why he does this. The real reason is that he felt that both told something there which he felt was important. He felt he couldn’t tell which was most important so he had both. “

That above reaction reinforces Bergman’s feelings and vision. Closer to the time she made it she revealed:

“The way I prepared was to read the script many times, to try and block it into sections. I would try to think, ‘This is the section where this is happening to her, and now he goes a little deeper in this section.’

“That is the way I very often work. I divide the manuscript into sections which always makes you know where you are shooting.”

Later on she elaborated even further:

“A lot of things I seriously didn’t understand. I just had to do it on feeling, on instinct. I couldn’t ask him because I felt so grateful he was giving me this, that I must pretend. When I see it now, I understand it so much better. I understand the character. But in a way I think it doesn’t matter because deep down we can experience even if we don’t really understand. I think you can instinctively play a character without intellectually or by experience being at that level. So many more people would appreciate him if they would dare to go in and think he’s really simple that he’s going to their emotions, not worry about the symbols.”

So with all these vantage points where does that leave us?

Conclusion: The Film Tears

One of the structural totem poles in Persona is an image of a film strip burning and breaking. It marks a rupture in the reality as its being presented, and it reveals to us, as a reminder the eyes through which this story is being seen (Elisabet’s son played by Jörgen Lindström).

When the film tears for us as viewers what are we left with? Is all theorizing to be tossed out the window? An interview Ullmann gives later on in her career when she took on Faithless as a director, based on Bergman’s screenplay:

Both women are called Marianne, so you can make all sorts of fantastic connections. Every viewer should have the freedom to do that.

Everyone also has the freedom to make connections with Elisabeth Vogler, I didn’t know very much, but I just knew I was playing Ingmar. That’s why I said that Max von Sydow could have played the part. I thought at the time “I will just watch Ingmar and I will try to act like him. In the current film, the character is called Bergman like the character he made into a woman and I played as Elisabeth Vogler in Persona. You can have great fun with this.

Which actually is not discordant with her assertions that “The real reason is that he felt that both told something there which he felt was important. He felt he couldn’t tell which was most important so he had both,” and that “So many more people would appreciate him if they would dare to go in and think he’s really simple that he’s going to their emotions, not worry about the symbols.”

If the film guts you it’ll pay to dig and pick apart these images and examine the interplay of the characters, the questions about reality, dreams, psyche, life, death, and sexuality. If it doesn’t move you an intellectual examination may not make it any better for you, and what would your motivation be to go in search of answers anyway?

When seeing the Repeated Scene in Persona you will think any of three things: a noble attempt at an experiment that fell short, a brilliant gamble that pays off in spades or a wasteful piece of sophistry. Many of the scenes in the film can be seen along this spectrum. It just bears noting to modern audiences that while his style, at-times starkness, look, and human dramas have become clichéd through the reverence of film students and arthouse filmmakers through the years, but many of the things he was doing were new and unique when he did them.

When the film tears for you as a viewer as Persona ends Bergman seeks for you to have been moved, to have thought and to have examined just as he moved, thought on, and examined his own life in its making. All else is fun, as Ullmann says, but there is no wrong. In this film Bergman rebelled against the tyranny of coherence and singular meaning and came out a victor, and we are all better for it; for now we have been moved.