The Arts on Film: Young & Beautiful (2013)

It’s no surprise that once again I find cause to write another one of these posts after having seen a new Ozon film. Though his love of 1960s French pop is as strong as it ever has been its really through the dissection of one artist’s particular work that we have underscored many themes, ideas and conclusions that are examined by this latest film.

Young & Beautiful tells a cockeyed coming-of-age story wherein a girl, Isabelle (Marine Vacht), after losing her virginity decides after a random solicitation to become a prostitute. Much of the film is about eschewing easy answers and furthermore rebuffing the notion that there is a singular explanation for her actions. It is rather not a mystery such as a investigation of characters and their reactions to given situations.

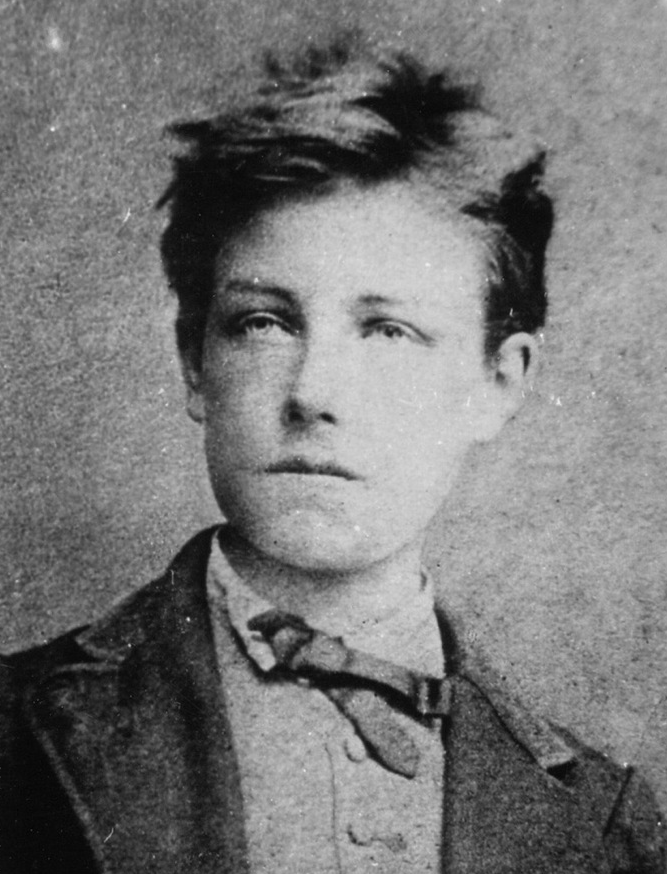

In many ways Isabelle’s tendentiousness to engage in such activity, her lack of compunction about it and the fact that she doesn’t really think about the consequences until things go very wrong are illuminated, or at least speculated upon, by dissection of the following poem by Arthur Rimbaud.

It’s not just the first line, but the explication by one student which surmises that there is no change only cycles that repeat really diagram a pattern of behavior that occurs in the film; not just by Isabelle necessarily but also by her family.

Ultimately, the film draws a similar schema to In the House in terms of familial claustrophobia, coexisting and commingling, but whereas it may be as intriguing intellectually, especially in the use of cited source material, it falls a bit short in the visceral arena.

Be that as it may, enjoy Rimbaud’s words free of the brilliant construction of Ozon’s scene and ruminate on them anew if you have seen the film.

Novel

I.

No one’s serious at seventeen.

–On beautiful nights when beer and lemonade

And loud, blinding cafés are the last thing you need

–You stroll beneath green lindens on the promenade.

Lindens smell fine on fine June nights!

Sometimes the air is so sweet that you close your eyes;

The wind brings sounds–the town is near–

And carries scents of vineyards and beer. . .II.

–Over there, framed by a branch

You can see a little patch of dark blue

Stung by a sinister star that fades

With faint quiverings, so small and white. . .

June nights! Seventeen!–Drink it in.

Sap is champagne, it goes to your head. . .

The mind wanders, you feel a kiss

On your lips, quivering like a living thing. . .III.

The wild heart Crusoes through a thousand novels

–And when a young girl walks alluringly

Through a streetlamp’s pale light, beneath the ominous shadow

Of her father’s starched collar. . .

Because as she passes by, boot heels tapping,

She turns on a dime, eyes wide,

Finding you too sweet to resist. . .

–And cavatinas die on your lips.IV.

You’re in love. Off the market till August.

You’re in love.–Your sonnets make Her laugh.

Your friends are gone, you’re bad news.

–Then, one night, your beloved, writes. . .!

That night. . .you return to the blinding cafés;

You order beer or lemonade. . .

–No one’s serious at seventeen

When lindens line the promenade.-Arthur Rimbaud

Ozon’s film has the occasional moment of truly striking beauty, which is undermined by the fact that our protagonist, Romain (Melvil Poupaud), who is diagnosed with a terminal case of cancer almost immediately never really lets his guard down, which is fine, however, the story could’ve had even more resonance than it does if we were allowed to see the family’s reaction to his death that they didn’t see coming. Aside from that it is a well-made film with some very great touches in it. The flashbacks are particularly strong. The theme of Romain wanting to take pictures of things and people he’s seeing for the last time is effective. Jeanne Moureau’s scenes are also quite good. However, in the end this film ends up being more impressive in its dealing with death than its American counterpart.

Ozon’s film has the occasional moment of truly striking beauty, which is undermined by the fact that our protagonist, Romain (Melvil Poupaud), who is diagnosed with a terminal case of cancer almost immediately never really lets his guard down, which is fine, however, the story could’ve had even more resonance than it does if we were allowed to see the family’s reaction to his death that they didn’t see coming. Aside from that it is a well-made film with some very great touches in it. The flashbacks are particularly strong. The theme of Romain wanting to take pictures of things and people he’s seeing for the last time is effective. Jeanne Moureau’s scenes are also quite good. However, in the end this film ends up being more impressive in its dealing with death than its American counterpart. Now the indirectness and hastiness with which the death, which I won’t talk about in great detail to avoid spoilers, in Little Men (1935) has little to do with when it was made. Some of the all time great tragedies and tear-jerkers of cinema come from the Golden Age. However, there were some films back then who briskly rushed through their endings to get to happy resolution to shave minutes off running time to squeeze more showings in per day. This is one good thing that multiplexes have brought on, you can stretch your film out if needed and not worry as much about lost opportunity for profit.

Now the indirectness and hastiness with which the death, which I won’t talk about in great detail to avoid spoilers, in Little Men (1935) has little to do with when it was made. Some of the all time great tragedies and tear-jerkers of cinema come from the Golden Age. However, there were some films back then who briskly rushed through their endings to get to happy resolution to shave minutes off running time to squeeze more showings in per day. This is one good thing that multiplexes have brought on, you can stretch your film out if needed and not worry as much about lost opportunity for profit.