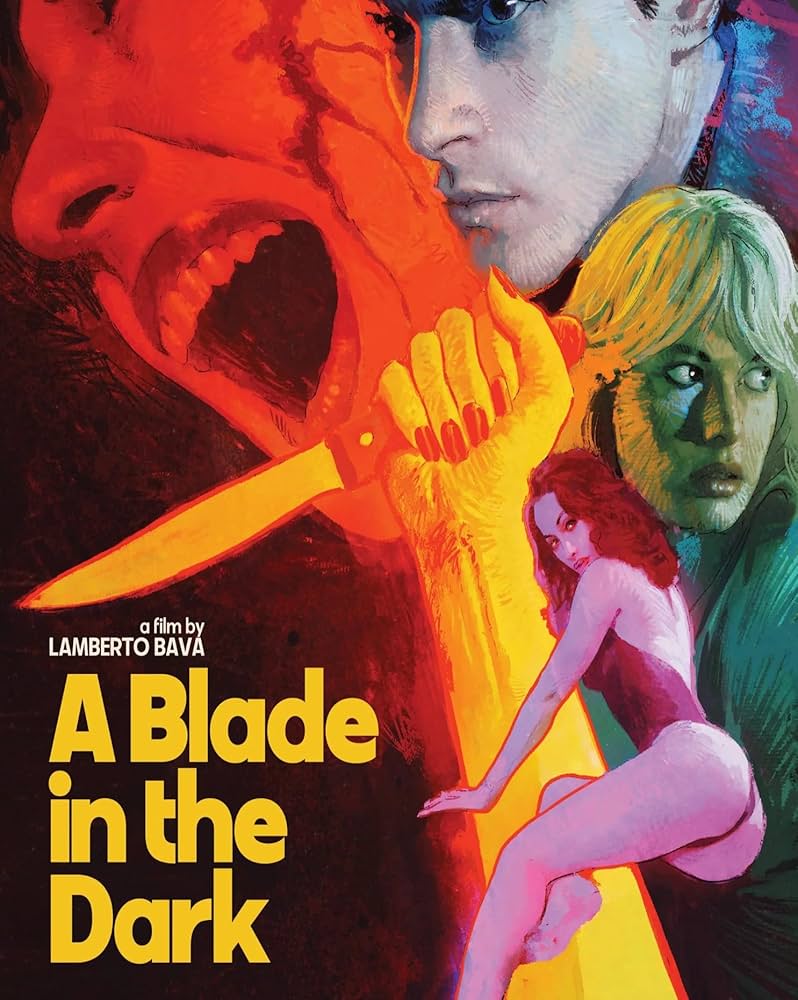

Journey to Italy Blogathon: A Blade in the Dark (La casa con la scala nel buio) (1983)

A Word of Caution

I decided to do a deep dive on this film. If you’re leery of spoilers it might be better to just scan this post. Although, I won’t lay the whole plot out in order in one section.

Also, this post is lengthy. I would’ve posted it in three parts if I hadn’t started so late.

Titles

Titles of gialli, and Italian horror films, are usually your first clue of how to take them. They tend to revel in the poetry of death, they might even come off as overwrought and florid to some. I personally love them. Sometimes the alternate titles work better than the more commonly used ones. Just a few quick examples: Mario Bava’s Bay of Blood, is a good title. The alternate, on the other hand, is an all-time great: Twitch of the Death-Nerve. Mario Bava’s father shot a film called La farfalla della morte (The Butterfly of Death). Most of Argento’s titles are memorable, especially those in the animal trilogy. You also have things like Pupi Avati’s The House with Laughing Windows. With regard to this film, the original title La casa con a scala nel buio loosely translates to “The House with the Dark Staircase.” Lamberto later went on to say he preferred the English title. And I must say, as disparate translated titles go, it is quite an evocative one.

Origins

Prior to making A Blade in the Dark Lamberto Bava, son of titan Mario Bava, had directed one feature, Macabre, which is an outstanding film that deserves a proper North American Blu-ray release. Just before making this film he worked as an assistant director on Dario Argento’s Tenebrae. The influence of Argento and that film on this one are clear. However, each stands on its own due to the disparate handling of similar plot elements, but the dialogue they share is intriguing. Any two works of art that dialogue with one another will fascinate me to some extent.

This film was originally intended as a four-episode mini-series. A televised event may have fit the structure better, but that would’ve made the piece more specialized and something only die-hards would discover later. It turned out that Bava tackled his subject matter with such verve and violence it couldn’t air on television. His producers then told him to cut it into a feature-length film, the original structure can be felt in the methodical pace of the feature-length cut as compared to many giallo films which are a bit more frenetic and byzantine in their construction. In preparation to write this piece I re-watched both the English dubbed feature-length cut and the Italian audio original and the pacing is perfect in the latter as it was structured to have each of its four parts end in a murder that is built to throughout; one of the many things that is far superior there.

Yellow Fantasies (Fantasie Gialle)

One thing that is often emphasized in writing about giallo films is that they are fantastical, if not outright fantasies. In the essay booklet of Vinegar Syndrome’s box set I was reminded of that. It’s almost as if each giallo and Italian horror film felt impelled to re-remind audiences unaccustomed to these films that, yes, they’re fantastical. Watch enough of them and you know it to be true.

When discussing Argento’s work, Guillermo Del Toro is practically awestruck by the fact that so many of his films function on a staple of the fairy tale he refers to as “the power of declaration.” Why is there a dance school run by witches? Why is there a room filled with barb-wire? Because there just is, I declared it.

Even in giallo films, which are more earthbound, there are things you just need to go with. One example would be, the first victim in A Blade in the Dark. She’s not bound or otherwise impeded from fleeing from behind the chicken-wire extending past a half-demolished wall. It could be fear that traps her, but that needs to be inferred. Her not attempting to flee once “stuck” also plays into a giallo trope I refer to as “the teasing blade.” Wherein the murder weapon tests a latch, keyhole, door jamb, or other obstruction the target hides behind methodically, slowly at times; Torturing the would-be victim and the audience alike. In this film’s first kill we watch the killer undo blouse buttons, pierce skin, draw blood, and dig. Giallo kills are more protracted than slasher kills that followed. More about stalking than chasing, the film is less concerned about body-count and more concerned about labored, shocking, outlandish kills.

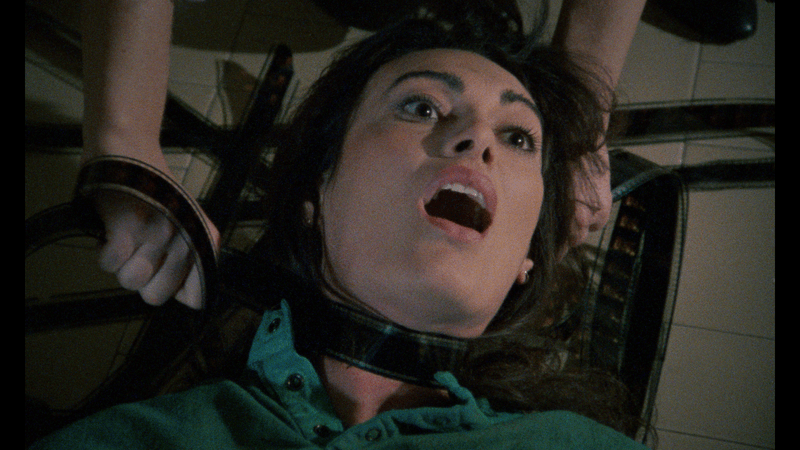

The exception to that rule in A Blade in the Dark is the bathroom kill. Typical gialli kills would have one flashy creative flare and that’d be it. This scene has multiple flourishes. It begins with the film’s most iconic bit of violence: the knife through the hand. It concludes with its most brutal coup de grace: a bag over the victims head while slamming it against the bathtub; then when the woman is practically dead, if not already there, the murderer slits her throat like she’s a slaughtered pig.

It’s safe to say this is the scene that kept it off television. A filmmaker wouldn’t want to compromise it for network censors. This scene, and the discovery of minor clues in clean-up later on, are just two of the elements in this film that remind people of Psycho. The other thing will be discussed later. While there are definitely problematic elements viewing it in the modern day, there are unquestionably many things that work about it and also many ways of parsing this film such that the aforementioned Vinegar Syndrome release’s booklet had three disparate short essays that didn’t even address my observations about it.

Another not-quite-realistic element is the women who pop-up uninvited at the house. Katia (Valeria Cavalli) is strange in general -a bit more subdued in the Italian audio- but is found in a closet by Bruno she’d come to retrieve her diary which was left there when Linda was staying at the house. Angela (Fabiana Toledo) likewise suddenly shows up wanting to use the pool, when Linda stayed she let her. Bruno agrees. She soon meets her end as well.

The Set-Up

The film begins with three young boys walking into a creepy abandoned house. They gaze down through the open basement door, a stairway that vanishes into darkness tempting them. One of the boys throws a tennis ball down the stairs, daring the blond boy between them to go down and get it. They taunt him, call out his fear. Here we get one of the most significant differences between Italian and English, and TV and feature versions: in the English feature version the chant they hurl at their target is “You’re a female.” It comes across as overly formal and tin-eared considering these kids are ten at most, aside from that its on the nose considering the plot that unfurls afterward. What they say in Italian is “Femminuccia” which translates to “girl” or “baby girl.” I don’t know if there was some decision made to match the “fe” sound in both audio and subtitles, but boys calling each other a “girl” or “little girl,” as the case may be, is not only a far more universal experience, but also less predictive than how it’s generally been played in English and in the subtitles.

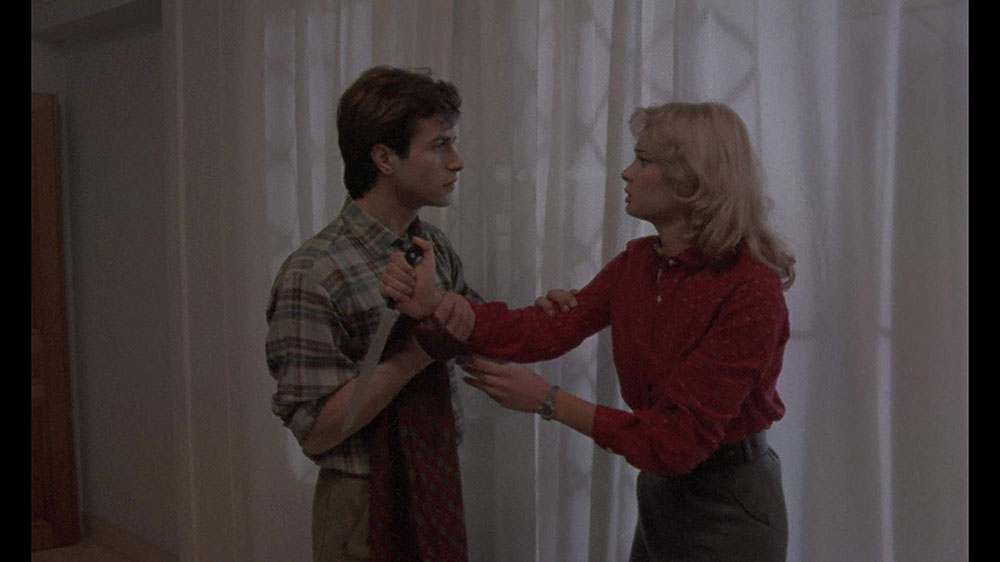

Regardless, after the tennis ball goes down the stairs, the frightened blond boy (Giovanni Frezza, best known as Bob in The House by Cemetery, and a staple in both Bava and Fulci’s films for half the ‘80s) disappears down the stairs. Then the tennis ball whizzes up the stairs, the other two boys avoid it. It leaves a bloody mark on the wall behind them. Shortly, after that we see a Moviola, Sandra (Anny Papa) and Bruno (Andrea Occhipinti, The New York Ripper) sit behind it. What we’ve been watching is a scene from a movie that Sandra directed that’s now being edited. The scene frightens Bruno. He’s tasked with scoring the movie. He’s nervous not only because the film frightens him but because horror music isn’t his usual metier. But that’s why she wants him. This is a great touch, not only does it put the protagonist out of his element artistically (he also is staying at what’s deemed to be a creepy house for inspiration), but Bava employs this very technique in scoring the film. He chose Guido and Maurizio De Angelis, who typically scored poliziotteschi films; a sub-genre of Italian action and crime films popular in the 1960s and 70s. Due to this choice A Blade in the Dark doesn’t sound like most other giallo films. The theme is melodic but not quite as entrancing as The Psychic (7 notte in nero), it has an electronic signature and layering, but isn’t anywhere as thumping as something like Suspiria. What it does is underscore the narrative perfectly and fit.

Bruno’s working in a house rented to him by Tony (Michele Soavi, who also worked with Argento and on to direct his own films) who seems a bit odd but otherwise harmless. Aside from creepiness, Sandra hopes the solitude will enable him to produce his best work.

Sexuality, Representation, and Art

One thing that’s well-noted in the booklet of essays is that the giallo wave was pretty much dead by the time this film was released. The usual purveyors of it went on to tackle other sub-genres of horror and thriller after this. By the end of the giallo wave the films needed to find varied and more creative justification for those being targeted.

While it’s possible to read this film according to a few theories of analysis, the main characters in this film operate from different places so I believe a layered reading of the film is necessary to truly appreciate all that’s going on.

The creators of this film were coming from many places here. As mentioned, Tenebrae influenced Bava here immensely. In Tenebrae, the killer raped/murdered a trans woman he was attracted to and then targeted other women. The first part of that equation is sadly all too relatable today and wasn’t unknown in the ’80s, but it wasn’t discussed as much in film. When it was handled it was done with the understanding of the time, and usually to some extent for shock value. Here, at least, as in Tenebrae, it’s intrinsic to the plot as the big reveal of the film is Tony is Linda, who is the murderer.

When the societal outcast is lashing out rather than an expendable victim (see the myriad movies referenced in The Celluloid Closet, many of which had LGBT characters who were tertiary and pointlessly introduced only to be immediately killed), it’s a lot easier to take despite any errors. Now, I am gay, not transgender. I read a post by a transgender writer about this film. Unsurprisingly, they find it transphobic, but they also said they wouldn’t tell people not to watch. I understand that ambivalence and realize that my thinking more highly of it has to do with my layered reading and personal background.

One thing that’s important to keep in mind watching older movies now is that they will have troubling content that might not age well, but they can still be viewed if you wish. I thought one of the best jokes on Brooklyn Nine-Nine was when Ace Ventura comes up Jake (Andy Samberg) says “Classic film. One of my childhood favorites. And it only gets overtly transphobic at the very end.” It’s a great line because it acknowledges a serious issue with the film while not discounting the work entirely. For gay and transgender characters to be the protagonist or survive horror films, they had to first be in them as more than tokens. This film at least does that.

Also, when a film is trying to do a lot, not everything will work for everyone. The fact that this film features a female horror film director is also significant. Sandra’s wardrobe is masculine. She wears ties and slacks reminiscent of Diane Keaton in that era, but that choice also speaks to gender expression being part of the plot. That her wardrobe not being commented upon also expresses an almost universal double-standard. If a woman wants to be more like a man, that’s fine to a degree. But a man or boy being more feminine, or being perceived to be more feminine, is a problem.

As I discussed some above, being an artist is also a central element to this story, most of the central characters are creatives. Bruno is a musician and composer; Sandra is a writer and director; and Julia, Bruno’s girlfriend, is an actress. Much of the film deals with the struggles of creation; Bruno trying to get the theme right, Sandra perfecting the film, and through Julia another LGBT reference is inserted in the film. She says her play has been suspended due to profanity. In the English audio she says the play is called “Sackville-West,” named after a correspondent and love interest of Virginia Woolf’s. In the Italian audio there’s an added line “Imagine a play by Mae West being obscene.” The reason for the obscenity charge is the play deals with “homosexuality in females.” Bruno’s response in both instances is “Oh, that explains it. No one wants to hear about that.” Whether Bruno agrees with the decision or he just means society in general won’t accept that almost doesn’t matter because they’re characters in a film that deals with something closely related.

The struggles of these three characters to create, the time they dedicate to it, their single-mindedness puts blinders on them. Bruno, is more interested in scoring this film and doing it well, while also solving the mysterious disappearances around him, than he is in self-preservation or working on his relationship. Similarly, Julia is too wrapped up in her play, and wanting Bruno to see it, to believe murders are even happening until she has not choice but to believe it.

That brings us to Sandra, who perhaps best represents the narcissism that all artists have to some extent. She betrays Linda’s trust, when she was told Linda’s secret it was made explicitly clear it was a secret. Not only did she turn that into the seed of an idea for a film but she repeatedly minimized Linda’s feelings and she was the offended party. Sandra also is hiding the final reel from everyone, no one is to see it presumably until the film comes out. There are stories of controlling directors doing things like this, but stopping the composer from watching it goes beyond the pale. Obviously, the composer needs to see the images his music is supposed to accompany. It also intimates that she’s on edge about Linda or that she realizes, perhaps subconsciously, that the story she wrote is more true-to-life than she intended. She even tells Bruno “The killer in this film is a woman” meaning her film but that’s also true of the one they’re in.

The Explication Scene and Linda’s Modus Operandi

The explication scene is perhaps the Achilles heel of many gialli, sometimes the denouement allows the audience to get the bad taste out of its mouth. In this film it’s literally the last thing you hear which is unfortunate. The explication is typically necessary due to the double-edged sword of a giallo film. The audience is kept from knowing the identity of the killer for a vast majority of it. The whodunit aspect is fundamental to its structure. With that set-up, and a killer who has an alternative sexuality, by default you have other people speak for them as in the case of this film both Linda and Sandra are dead in the end. Add to that writers who are attempting to make a statement and be original and you get the kind of inaccuracy you find in this film. A lot of gialli also leaned on a pop-psychology that treated trauma as a kind of “Rosebud,” if you discovered what happened to this person you’d understand everything about them. That works to varying degrees in the genre. Even in a fantasy its hard to accept that one’s gender identity or sexuality will change because of bullying, but those taunts can make one see one’s self more clearly. Similarly, being unable to accept one’s queerness, however, is accurate and a universal phenomenon.

Not seeing the killer, not being anywhere near their headspace, one must also speculate on the plan Linda had in mind. Getting past the filmmaking elements and the surprise of the narrative into the idea Linda had is not hard. She and Sandra had a falling out. Linda told Sandra about her deepest trauma in confidence. Sandra decided to spin that story into a film using Linda’s story in a scene. Linda got upset. Her confidence was betrayed, the friendship ruined. It seems Linda’s initial goal is to ruin the film. She, as Tony, rents out the house to man people, including now Sandra’s composer. She whispers so Bruno can hear it on playback telling him eerie secrets, she then destroys his takes of the score, halting his work to make him start over. None of that deters him. Then the unexpected houseguests dying doesn’t stop him either.

Linda then finds the film’s elusive final reel while no one is looking at the post production facility. She lops off half of it and slices the rest to ribbons. None of it stops Sandra from trying to tell the story she wasn’t supposed to tell.

Aside from betraying Linda’s trust, Sandra was essentially outing Linda in her film, so why wouldn’t she want to get her revenge? She could stop at ruining the film, but then it wouldn’t be a giallo; the revenge fantasy aspect wouldn’t be as viscerally appealing. The fact that Sandra is strangled by a strip of 35mm film and then found in the remainder of the final reel is ham-fisted, perhaps, but it underscores the point that Linda wouldn’t have felt pushed to do this without the film. Giallo films are about excess and many times that’s just the kind of excess I want in a film. If it seems like you’re gonna go there, really go there!

At one point, Bruno and Sandra find in a room that was previously locked. It contains two collections of items traumatic to Linda in cardboard boxes: pornographic magazines (which could be a nod to her body dysmorphia without the film having the vocabulary for it. Early in the film she slashes at the centerfold in a nudie magazine when she first enters the recording studio), in the second box are tennis balls. While this is striking as an orgy of evidence, those are rarely found in reality, but this is a fantasy. Furthermore, I really love that Linda seeks to weaponize these traumatic totems. She also uses the taunt the bullies used on her (“Feminuccia“) on one of her victims.

The score at one point I feel comments on Linda also. I previously mentioned musical overlays. Toward the end of the film the emblematic theme is played, then another piece of score plays over it. This is disconcerting for the audience but also can be read to represent the clashing of Linda’s personalities.

Conclusion

Sex and sexuality are and were vital cogs in giallo films. As opposed to the slasher films they inspired in the US, there wasn’t as puritanical a bent, nor was the sexuality typically superfluous to the remainder of the story or themes. Neither is something like A Blade in the Dark totally out of left-field. In her essay “The Mother of All Horror: Witches, Gender, and Dario Argento” Jacqueline Reich wrote that giallo is “a genre dominated by sexually ambiguous villains and monsters offering cross-gender identification.” And I certainly agree with that take. Machismo or toxic masculinity has always made me bristle, so giallo characters (or those in any genre) offering a counterpoint to that intrigue me.

While Bruno’s simplistic interpretation is that Tony’s masculinity was stunted, Linda’s whole being was affected. One final comparison between English and Italian audio, there comes a point where Linda loses the box-cutter she began her spree with. When she enters the kitchen and finds the knife-block displaying the knives vertically on the wall, there’s an ecstasy in Linda’s vocalized reaction that’s half-shock (like she sounded after the bathroom kill) and half-arousal. This also plays into ambiguity, as does the fact that in order to enact this plan Linda has to inhabit the body and clothing of her former persona more often. That definitely explains how uncomfortable and nervous Tony is, and why he goes out of his way to say he’s not just leaving the house, not just leaving Tuscany, but heading to Kuwait on non-existent business.

The ingredients of many gialli, especially Tenebrae—sexuality, representation, and art—are in this film with a different recipe. Lamberto Bava wondered what if the trans person had been wronged and snapped. To answer that question and produce a film about in 1983, in Italy, it almost had to be in an exploitative genre as it was one of the few refuges to more fully examine outcasts. There is certainly more to A Blade in the Dark than meets the eye.