Once Upon a Time in the 80s: The International Scene (Part 6 of 17)

One can never really analyze all of international film during a given decade given the enormous scope and the amount of films released worldwide in any 10-year period. Certain decades have cinematic movements within given cultures; the 1960s are perhaps the most notable with the nouvelle vague influencing all of Europe. However, the 1980s is the time when foreign films started to have staying power. The art houses would soon be cropping back up and Americans started to be more willing to watch foreign films than ever before, even in the 60s watching Fellini and Truffaut was a sect of counterculturalism that was not universal.

The Academy Awards have always been a promotional event. The press has added a great deal of importance to them and the public have followed it making it consistently one of the highest viewed television programs every year. Thus, when the Academy, whoever they are, starts nominating foreign films in categories usually reserved for American films one needs to take notice.

In 1983 Fanny and Alexander, what was said at the time to be Ingmar Bergman’s last film, received six Oscar nominations and walked home with four of them. Ironically, the categories in which Bergman should’ve been given the awards (Director and Screenplay) were the ones they didn’t win.

Later on La Historia oficial an Argentine film was nominated for best screenplay in 1985. In 1988 Marcello Mastroianni was nominated for Best Actor in Dark Eyes and the screenplay for Au Revoir les enfants and the director of My Life as a Dog, Lasse Hallström, were nominated while Babette’s Feast won Best Foreign Language Film. Also, amongst the nominees was a great piece of Norwegian folklore that has been handed down over the generations called Ofelas.

Max von Sydow received an academy award nomination for his performance in Pelle the Conqueror which was in 1989, for a 1987 release. This was a film which won the Palm d’Or in Cannes, and it is truly one of the best films to come out of any country during the 1980s. It takes place at the turn of the century when Lasse (Von Sydow) and Pelle (Pelle Hvenegaard) arrive in Denmark from Sweden to try and find work for themselves. We follow their trials and tribulations that make us as the audience feel more and more sympathy for the characters as the film progresses. Part tragedy and part triumph, this is a beautiful film that rightly put Bille August on the map.

Of course, we also get Giuseppe Tornatore who’s one of the most talented directors in the world right now coming out with his first hit Cinema Paradiso. In France there was the cinema du look but the emerging nation of the 1980s was Brazil.

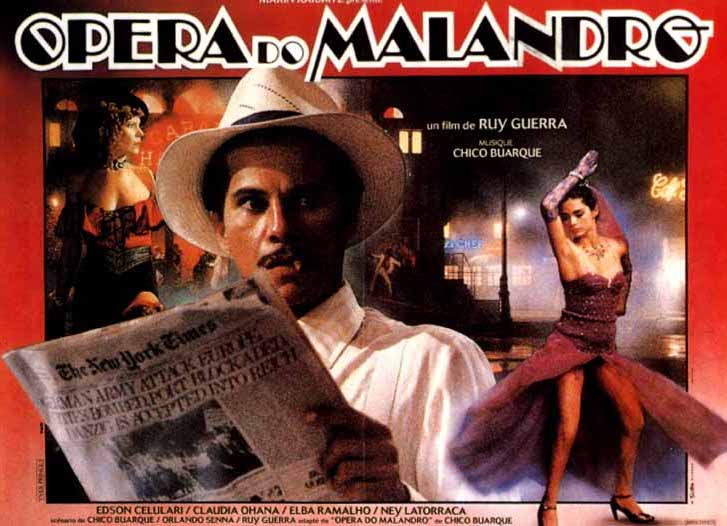

While the film industry was beleaguered when the government cut off all funding for the arts during an economic crisis there were two big films that set the stage for the international success Brazil would enjoy in the 90s and 00s with films like O Quatrilho, Central Station and O Que e Isso Companheiro? (English title: Four Days in September), A Partilha and Bicho de Sete Cabeças. First, there was Pixote a powerful film about juvenile delinquents from the favelas of São Paulo, of which none were professional actors. It’s a gut-wrenching dramatic experience and an amazing piece of simulacrum; in a sense the Brazilian neo-realist film. The film is told in two parts: first, we see the minors and their struggles in the juvenile camp. Second, there’s a break and they escape and we see their life on the street. Hector Babenco, a naturalized Brazilian, struck home by portraying poverty and crime as well as bureaucratic corruption as it was never seen before in Brazil. It ever landed on many American top 10 lists.

Meanwhile, Arnaldo Jabor’s Eu Sei Que Eu Vou te Amar is a direct victim of the government’s cutting artistic funding and they had to work on practically no budget. This film demonstrates not only the power of editing but also of fine acting. There are only two actors in this film and they are great so much so that Fernanda Torres won Best Actress at Cannes in 1986. We meet the two main characters and they have a discussion and an argument about their relationship why they got divorced. There are flashbacks and a video monitor with the actors on them represents their inner-monologue. The dialogue in this film is fantastical. There’s a stream of poetry that come out through these inner-monologues that is just perfect and the arguments are intelligent and not just bickering. The film is absolutely riveting and is as the blurb describes “a psychological playground” that only suffers from the hallucinogenic end.

International cinema finally made its presence felt for good in the nation that influences the world. Whether negatively or positively most cinematic movements around the world are reactions to Hollywood, and the constant presence and acceptance of international cinema is a necessity to the vitality of American cinema.