Foreign Language Film Issues 2013: Hollywood Rules (Part 4 of 5)

As has been the case in years past I will here look at some of the issues plaguing the Best Foreign Language Film nomination process at the Oscars. Since this year I am touching on a large array of interrelated topics I thought it best to post my thoughts in a series. To read the introductory post of the series go here.

This text picks up immediately where the last part left off.

Hollywood Rules

It has been suggested that the Academy, or an offshoot thereof, should select the foreign films eligible. My newest suggestion will feature a compromise on that notion.

However, it is worthy of consideration of the fact that, no matter what amount of importance or disdain you view the Academy with, this is their awards. There was a time when the cinematic revolutions worldwide filled independently-owned movie theaters and had the college set watching and artsy-er breed of cinema, but times have changed. Therefore, taking a hard look at what the Academy is short-listing, and ultimately nominating and why, is something we and national committees should be doing. If the films being chosen with the Academy in mind is this just not cutting out the middle man? I’m not a fan of playing Devil’s advocate, which is what I was doing there, but I can’t find a lot of room to argue against it; save for the fact that I don’t care for it much and have an alternate idea, which will be presented in the final installment.

The Golden Globes, really?

If you follow critics and movie geeks on Twitter, or even if you just Google The Golden Globes and find some brutal op-eds on them you’ll see how dubious their nominating process is. This is excluding the fact that the membership is so small. Yet, even this much-maligned body accepts multiple nominations from nations, but the Oscars can’t?

Release

The Academy this year disqualified Blue is the Warmest Color, which is a Palme d’Or winner and one of the most talked about foreign arthouse releases of the year solely on the basis of the fact that its release date IN FRANCE was too late.

One recent argument that has emerged is that a US release date should be a requirement. That has its pros and cons, but surely if a film has seen European festival dates and has already seen a US release that qualifies it, how can you disqualify it because of its domestic release date. It’s beyond counter-intuitive.

Eligibility for Oscars in Other Categories and Snubs

While on the topic of snubs that brings related topics this year. I’ve not yet seen the film, but have seen fairly universal raves and lauds for Lea Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulos in the aforementioned Blue is the Warmest Color. Due to the fact that the Academy has ruled said film ineligible for Best Foreign Language Film it is also ineligible for other categories.

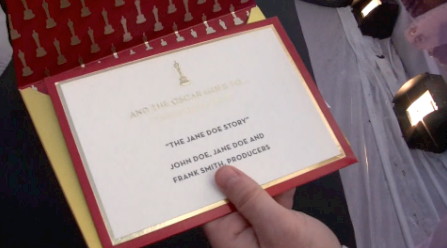

Yes, there have been instances of foreign films being nominated for multiple awards: three instances jumping quickly to mind would be Amour (5), Central Station (2) and Fanny and Alexander (6) in all those cases those films were submitted as the foreign language selection for their respective nation, therefore, eligible in additional categories. Any snub this year can also write off any chance at nominations in ancillary categories.

Committee Submissions

With all the case-studies discussed prior, and with most countries I’m sure; it’s a small body making the decision of which film to select. Whenever you’re dealing with a small body I get the feeling, even though I was offered no proof of it, that undue influences could affect outcomes. I’m not saying they haven’t; it’s possible. I think most people who watch film and know the mechanics understand that the “best” isn’t always sought out. Sometimes it’s the most commercial, sometimes the most “Oscar-friendly”, sometimes other factors can be seen as coming into play.

This series will conclude tomorrow with part 5.