Is This Really Contrary to Popular Opinion, or Why Choose Song of the South

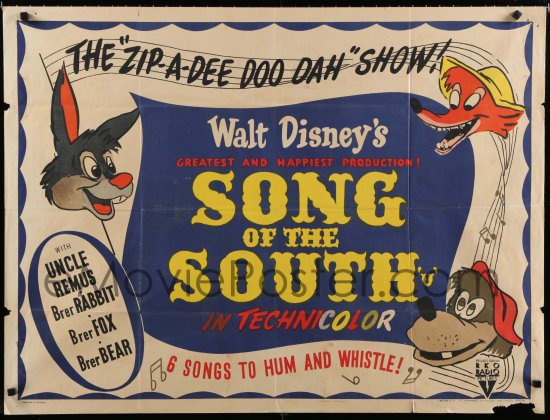

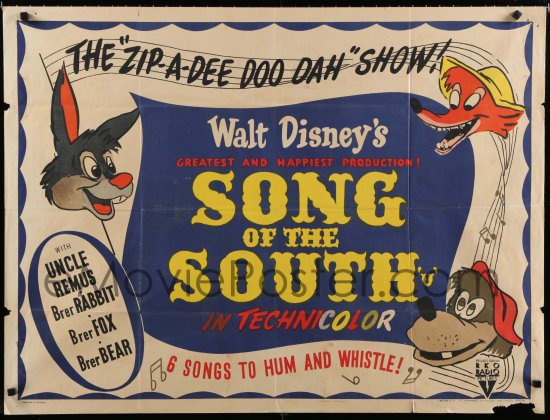

In the course of this brief examination of Song of the South I hope that the only mea culpa I have to write is about the fact that my enjoying this film is not a minority view. Usually, when I’ve seen discussion about the film on Twitter it has been by people who also have a fondness for the film, and are film people. However, the mere fact that it is Disney, the very company that produced the film that is doing the suppressing is a large part of the issue in my mind, and part of why it feels like an unpopular opinion.

The film is one that Disney produced in the mid-40’s, had a mixed reaction, and early detractors, the NAACP included, but was not a title Disney ran from until the 1980s, after its second re-release in theaters it was gone from American home video in the mid-’80s. Later on “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” was even expunged from Sing-Alongs. However, one of the many aspects about this disavowal is the fact that Disney picks and chooses where and how it will shun the film. It will not distribute the film in the US, but it does still sell overseas; it will make one of its more popular Disney Wold rides about it, but it won’t include Uncle Remus or try to enlighten the park guests who is on the tee shirt they’re buying. They will have many pop singers reinterpret its iconic theme song, but no longer play the version from the film.

In the past Disney liked to used to play the “you misremember” card. With the advent of video and the internet that holds less water so editing and suppression have become the norm for certain things that have made people squeamish. While other projects, also fairly common to all forms of entertainment in their era are addressed via contextualizing disclaimer usually delivered by Leonard Maltin on a DVD collection.

In the interests of further fully disclosing where I am coming from I will say that yes, I do consider myself a fan of Disney. One of my blog’s theme topics on an annual basis is an examination of Disney fare. However, in an age of fanboydom it seems like you can only be a cynical chronic complainer or a blind follower. I’ve always equated following a studio, especially one that’s part of a large corporate armature, to be akin to rooting for a sports team: you like them, you want them to do well and right, but you’re not blind and they are not immune to being criticized by their patrons.

It’s not as if Disney has never had to deal with these questions even from their stockholders. It has come up rather frequently at annual meetings. There’s more on that and many other of the stories I will touch on here in Who’s Afraid of the Song of the South? a great book I read in preparation for this blogathon. I recommend you check it out if you have further interest in the topic.

“Somebody has to kill the babysitter.”

Television and Film as surrogate parent or babysitter is not a new concept. The quote that is in the inspiration for this heading is from The Cable Guy (1996). In that film this is the line that divulges the modus operandi of Chip’s psychosis. When this film was made the over-emphasis that some believed TV and Film had on society, or on certain individuals, was not a new debate. However, one of the points that the film is making, even in all its silliness, is that it takes a deranged sort of delusion to really use film or TV as an analogy for real life or to get it to substitute things like parenting, conversation, thought and other things. The climactic events of the film take place as the nation hangs on the live broadcast of a famous murder trial (a subplot which brilliantly spoofs the Menendez case). What this is all leading to is that one of the things that Song of the South has had to contend with, which was not a problem of its own making was the overemphasis that depictions in the media have been given on the formative process of human beings as they pertain to attitudes towards racial groups, women and the like.

I use the word overemphasis because I cannot argue there’s no impact, but it is almost never the main cause of a prevailing attitude. Those who have cited video games, movies, or TV as motivation for crimes have usually had mental issues that impaired their grasp on reality. Part of the issue stems from the fact that oftentimes a film or cartoon with dated material or material that can be interpreted as offensive are usually seen by children who are not monitored. In essence, removing the potentially offensive work of art is pandering to the lowest common denominator: the “impressionable child” watching something unsupervised.

Singled Out; Other Things are Never Questioned and Readily Available

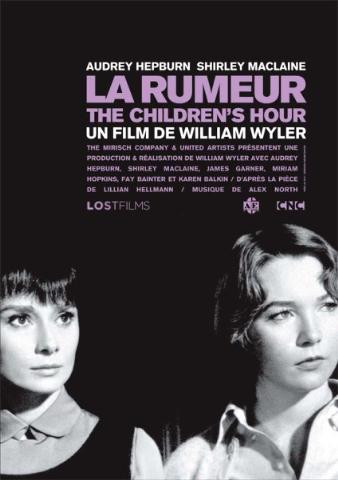

Yet, aside from some short subjects this is the only Disney product that has been struck in its entirety. Disney’s corporate penchant for self-editing and censorship is usually in smaller moments but rarely involve making a title wholly available. Other films, even from the selfsame studio, have references or depictions by today’s standards that are wholly unacceptable but they’re still widely consumed without a second thought. One of the more notable examples is Dumbo. Aside from having its scary moments I am mostly referring to the crows. The characters are crows and clearly voiced by African-American actors, which can be construed as a reference to Jim Crow laws. However, the availability of Dumbo has never been threatened. Disney has never shied away from the title as a whole. Yes, the crows are absent from the Dumbo ride at Disney world and their songs (Namely “When I See an Elephant Fly”) are rarely collected and re-released despite being one of Disney’s finest musical creations. The Simpsons made a brilliant joke about this, Lisa asked if Dumbo was the film that had “those racist crows in it?” Homer responds “Oh, Lisa, those crows weren’t racist the men who animated them were.” Which is what a lot of this boils down to: it was a different era so the necessity of sensitivity, and the level that needed to be reached to be seen as progressive, was lower.

In watching documentary footage on a Little Rascals box set you hear speak of the progressive move it was to have characters like Buckwheat and Farina who played with white children as equals. In a nation that still had segregation and other discriminatory practices in play, yes, relative to society that was a utopian vision. Even though a lot of the dialog and gags those characters have are what most date their films relative to its own era it was a step forward. Back then it was a bold statement today children of different races playing together is far more common, as it should be.

In the ‘90s certain Bugs Bunny cartoons like Hillbilly Hare for one were taken off the air after complaints were lodged to Cartoon Network. Yet, to my knowledge the short where in Bugs sings “One, Little Two, Little Three, Little Injuns” as his tallies his arrow-hits and then corrects himself to mark one as only half a hit because “that one’s a halfbreed” never was removed. That fact is brought to attention because those who know of the cartoons know these facts, but they don’t get the notoriety the Disney titles get for equal or lesser offenses. Looking at the whole landscape of animated shorts from these eras ethnic stereotypes were common, broad and not unique to one studio. Even with these occasional lapses in judgment (by modern sensibilities) it doesn’t really change Bugs Bunny’s character. He was wisecracking and had a mean-streak at times but he was always the retaliatory figure in his conflicts. Only on occasion like in the aforementioned short or in his battle with Giovanni Jones, the opera singer did things go too far. Woody Woodpecker over at Universal on the other hand was an instigator but still made of similar stuff, maybe a little more unhinged. Getting back to the Disney realm, one correct modern interpretation is actually found on a t-shirt you can find at Disney World gift shops with Donald Duck on it, which cites him as the original angry bird.

In Song of the South, even accepting the fact that there are some miscalculations the bottom line is that Br’er Rabbit and Uncle Remus are undoubtedly heroes of the story. I used to attribute most of the notion that the film was racist to the Tar Baby sequence, which as I discovered when watching this film was and is a phrase and a fact of life in the South before it became a racial slur. Much of the belief that the film is racist stemmed from the fact that Disney did not add a title card establishing a postbellum time period. Thus, some believed it was antebellum and not postbellum. It’s an unusual miss though from an audience that frequently had to infer and decode as the Hayes Code made filmmakers get creative about such things so they could deal with adult issues in films without being overt.

One thing that Who’s Afraid of the Song of the South by Jim Korkis goes into a good amount of detail about is the pre-production process. Many of the errors and perceived errors in the making of this film can be attributed to Disney playing both ends against the middle. The first writer (Dalton S. Raymond) they hired with a mind to be true to the source material. Then after some battles about certain elements like his use of the word “darkie,” which Disney sought to avoid they hired a leftist Jewish writer (Maurice Rapf) to try and balance it out.

If you want a troubling depiction of the South and slavery set before the war watch Way Down South which I discuss here. There’s no move from any entity to strike it. On a more noteworthy level Birth of a Nation both received protests upon its release and spurred and increase in popularity of the KKK. The next decade (the 1920s) was the zenith of its membership numbers. It is in the public domain now so it would be hard to suppress, but it’s still very easy to find.

Segregation and Other Truths We’d Prefer not to Address

Part of this whole issue is that we like to pretend there’s no racism in America. If we didn’t how could someone seriously have coined the term post-racial with a straight face almost entirely based on one election result? Song of the South was made in an America that was still segregated, thus, in some ways racism was still government-sanctioned. Furthermore, its premiere was in Atlanta meaning that many of the cast members were not even in attendance because the premier venue was “Whites Only.” So clearly almost any film made in this time will likely reflect racial attitudes that are no longer prevalent or acceptable. But just because its not the norm, or frowned upon, does not mean that racism has been eradicated.

Slaves being emancipated, didn’t end the discrimination against blacks in America. Neither did the Civil Rights Act. Nor did the creation of the term Post-Racial. However, unless some incident sparks the debate like Ferguson we choose not to have the discussion. Film has always tied art and business and with the corporations running the big studio being larger than ever the gut instinct more than not is to always be safe and never be sorry.

Splash Mountain

Splash Mountain is perhaps one of the most iconic rides at Walt Disney World. The theme parks are like an embodiment of the Fantasia ideal rides (read segments) have been switched out but the basic premise remains the same. The planning of the ride, like anything Disney, is well-documented in lore. There was much discussion and it was decided that all the animal characters could and should play a role in the ride, but Uncle Remus, the center of the film, should be omitted since it was his persona, his perception by some as being an Uncle Tom, which much of the controversy around the film swirled. Because the fables in which Uncle Remus and his cast of animal friends were a part of are no longer as well known as they once were there is no frame of reference for younger patrons.

However, what happens when he’s hidden is that Disney really ends up misrepresenting itself and baiting-and-switching its consumers. There are are people riding it who have no idea there’s a film behind the ride, many likely leave believing that Br’er Rabbit, Bear and the like may be created for the ride like Figment was for The World of Imagination in Epcot. It’s another case of Disney wanting to have its cake and eat it too: because the film is deemed misrepresentative and offensive to some in the US market we will not make it available on video there, but we will make it available in many foreign markets, exploit the song for CD sales and the other characters for a ride.

Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah

Lawrence Welk, Xavier Cugat, Freddie and the Dreamers, André Previn, Bing Crosby, Doris Day, Debbie Reynolds, Mannheim Steamroller, Dionne Warwick, Johnny Mercer, Rick Ocasek, Steve Miller, Los Lobos, The Jackson 5, Miley Cyrus and many others have recorded the song. Many of them on Disney released albums. Disney has even still included James Baskett’s film version on some collections. The only apparent retraction of the song was removing it from a Sing-Along collection on later editions. It’s just another case of Disney being inconsistent. They still want to be able to profit from the movie, but not actually make the movie available.

The Split On the Film Has Always Existed

Upon its release the NAACP issued a statement on what if felt about the film much of their interpretation was shaped by the areas Disney left vague. The point being really that that reaction was immediate and not revisionist or in hindsight. It’s only many years later that Disney decided it would start to err on the side of caution to protect their brand name and assuage the detractors of the film and make the film hard, if not impossible to find in the US.

It’s Consistent with Disney

However, the unfortunate part of this story is that it’s just the most notable example of Disney’s in-house censorship. Many of the stories Jim Korkis tells are about films being altered, edited or otherwise modified because certain things years down the line may have been deemed objectionable.

Among them are the car crash in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, characters being digitally removed from Fantasia and shorts disappearing because they were wartime propaganda, and there are many more.

Disney Buried RKOs Swiss Family Robinson

Here’s a small tidbit about Disney that really irks me, and it goes back to suppression: when Disney was preparing to make Swiss Family Robinson they made sure they acquired all the copies of Swiss Family Robinson (1940) produced by the defunct RKO Radio. The purchase was made simply because Disney didn’t want the versions compared. Now, this is not an act too dissimilar from repeatedly optioning a story, or many stories, simply so your competition can’t have any. However, where it falls into suppression is that the original they wanted hidden is now 75 years old. They audience for it, and even for Disney’s version has, dwindled. No one can see it now, it’s not impossible that the film is now lost for all time just to continue to protect the business interests of a 55 year old film.

Rerelease Madness

Song of the South is a property that Disney didn’t cool on immediately. It was later on, when Walt was gone and the company was bigger, more successful and more corporate than it was during and just after World War II. A comic strip story was the topic of some internal debate in the 1970s, ultimately it was printed and came and went without incident. A clip from the film was featured in an episode of the Disneyland TV show a decade later. More telling is the fact that the film was, like many Disney films, rereleased on multiple occasions. The difference here was that there was more of a layoff. The film again saw the light of day in 1980 and 1986. It was released on VHS in 1986 but has since been further and further barred from the pantheon.

Conclusion

Perhaps what should really be asked is “What is gained through the suppression of Song of the South?” If there’s one thing that many recent headlines have proven is that freedom of speech is still under attack, and many of us who are fond of the arts and making a living therein are willing to fight tooth and nail to defend the right to speak. The argument that passive racism is more pervasive and harmful than overt racism is a fair one. In my estimation there are cinematic trends that are far more harmful than one interpretation. If you look at the landscape of films most award-nominated performances for African-American actors are still Civil Rights or Slavery-themed films. Films without award aspirations usually still cater to stereotypes that are not new. The Help may be a film that was divisive, but regardless if your outlook on it is positive or negative it is still about domestics as well-intentioned as it is. The point I’m driving towards here is: Song of the South had good intentions that were muddled in the the production decisions, and furthermore through interpretation. There are far more obviously troubling titles that never get questioned.

The expunging of history, and formerly accepted attitudes, many of which still exist, do not change the fact they once existed. If there’s one thing that history, or even the nightly news proves, is that ignoring problems does not make them go away. Even in its condemnation of the portrayal of African-Americans in the film the NAACP did commend the filmmaking at play involved, and the Academy followed Mr. Disney’s suggestion and gave him a honorary Oscar. Correcting the notion that this was an antebellum tale lessens much of the issues. The costuming was another aspect that in reading the book I had to roll my eyes. If the white characters had been more threadbare and destitute in the throes of reconstruction as they had been described as in the script the notions of class and master-slave relations wouldn’t have been able to take hold. That doesn’t alter the fact that these children are taught sage advice, and helped out greatly by Remus more so than their parents can.

While I’ve gone over the finer points and discussed how the film has been construed as racist, and where I believe more deliberate decisions could have been made to make the facts and points of the narrative more clear; I do not agree with its assertion that its racist. I have not been able to get past Birth of a Nation’s introductory shot of African-American characters sitting on a porch eating watermelon. There it’s not the kind of offense I can roll my eyes at and continue Propaganda films are still available to see in more cases, highly uncomfortable to sit through and at times more uncomfortable because of how effective they are like Triumph of the Will. However, these are opinions I’ve formed by seeing all or part of this film. I’ve seen Song of the South on multiple occasions. Those who have seen it and contend it is racist are at least informed by their interpretation of the film. As Eric Vespe of Ain’t It Cool News points out, the gatekeepers who keep the film hidden are not as informed:

I was speaking to an ex-Disney executive a few years ago at a film festival and I brought up Song of the South. We had been watching a lot of films together over a couple of days and I decided it was okay to broach this subject. After all, this unnamed exec seemed very smart and obviously cared about cinema.

My big question: “When do you think we’ll ever see Song of the South on DVD or Blu-Ray?”

His response: “Never.” I asked why. “Because it’s racist,” he exclaimed.

I know that’s the general perception of this film, but I was still taken aback. I thought for a second and asked, “Have you seen it?” Incredibly he said he hadn’t and that right there is the root of the problem. People see the Tar Baby image or remember Uncle Remus as a slave, which is wholly incorrect. The film is set during Reconstruction and Uncle Remus is a free man. In fact all the people working on the farm are free.

The heart of the film is Uncle Remus’ friendship with the white kids, played by Walt Disney favorites Bobby Driscoll and Luana Patten. Their characters didn’t see Uncle Remus as black or a lesser person. He was a friend.

Someday someone at Disney will realize there’s a way to release the movie to home video. Harry had a good idea to have someone like Spike Lee put the film in context with a specially filmed intro. It’ll take something like that, which is a bit of a shame. It’s also a bit hypocritical since they aren’t afraid to monetize the cartoon characters and the infamous Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah while pretending the actual movie they come from doesn’t exist.

Dated and inaccurate portrayals where they are found are different than a film that is in its entirety a racist construct. Furthermore, there is a bottom line notion that every film is a film of its time. Disney here becomes a victim of its own marketing where titles are branded as classics prior to even coming out. There’s also a fallacy of timelessness, of unchanging social mores and that everything will always be the same. Nothing is ever the same. A popular film notion has always been “They don’t make them like they used to.” Recently I saw that amended to read: “They don’t make them like they used to and they never did.” Film is an ever-changing artform just as society continually adjusts our interactions, laws, politics, etc. Therefore, how can a film made nearly 70 years ago ever be acceptable by current standards of anything. Context always matters, and discussion is not bad regardless of what side of a topic you land on.

That puts a button on the final point of the last argument. I feel if anything Disney was trying to make its point in not-so-many words. The problem there, especially when things were usually more didactically done is that it can be misconstrued. However, just because something makes us uncomfortable or can be difficult to discuss doesn’t mean it should go away. Ignoring problems doesn’t make them go away as we’ve been forced to rediscover many times over. I happen to be pro-Song of the South. However, even if I was against it and thought it to be a harmful representation, I would not be in favor of its being made unavailable. Too many films are lost to the ravages of time and chance. Where other arts enjoy more permanence film remains fragile in this regard and we should not wilfully remove films from existence just because some may dislike it. It’s a part of cinematic history and our history that should be readily available.