Ingrid Bergman Blogathon – A Tale of Two Bergmans: Autumn Sonata (1978)

Introduction

This is my, sadly late, contribution to the Ingrid Bergman Blogathon hosted by The Wonderful World of Cinema.

When I saw this announced I knew there was only one selection I could really make. Granted my recent Blogathon contributions about Images by Ingmar Bergman, and Interviews: Liv Ullmann, combined with my recent acquisition of the Autumn Sonata Criterion edition made it a natural choice.

However, this is a film I loved since I first saw it, and one of the rare Bergman films I saw in the theatre first. This was thanks to a retrospective the Film Forum had a while back.

So with the new Blu, the supplements, and all the other sources I could cull from, it really did open up a world of new insights into the making of this wonderful, heart-wrenching film.

Images: My Life in Film by Ingmar Bergman

As I stated previously, Bergman’s book Images is perhaps a better source for his notions of his work as he had the benefit of hindsight and didn’t have as close an emotional attachment to the material, and whatever emotional scars production may have left faded over time.

It’s always fascinating to get into the creative process. Bergman shares much of his for this film. He states “Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullmann were necessary for Autumn Sonata.” As the idea was born first that he wanted to work with Ingrid, then as this idea occurred to him it seemed it was the perfect vehicle. And it was.

Much as Stephen King describes the construction of The Langoliers, Bergman speaks of how easily the story seemed to flow from him: “Autumn Sonata was conceived in one night, in a matter of hours, after a period of total writer’s block.”

It came about in manner not dissimilar to Robert Rodriguez’ theory about obfuscating what film is in fact a director’s second. With regards to Autumn Sonata Bergman stated:

I wanted to have something up my sleeve in case The Serpent’s Egg flopped with a somersault.

The title of the film makes sense as per the dictionary definition of sonata:

noun, Music.

a composition for one or two instruments, typically in three or four movements in contrasted forms and keys.

Bergman similarly wanted to limit the number of characters in the drama:

“Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullmann in the two roles, and no one else. Eventually there may be room for a third character.”

In terms of major speaking roles he succeeded in this aim. In production many of the alluded to flashbacks do occur giving bodies, if not voices to those characters.

Bergman speaks of how he feels ultimately the film was a failure due to the fact that “A French critic cleverly wrote that ‘with Autumn Sonata Bergman does Bergman.’ It is witty but unfortunate. For me, that is.” He felt this was accurate going on to further state that:

“I also feel that Tarkovsky started to make Tarkovsky films and Fellini began to make Fellini films. Yet Kurosawa never made a Kurosawa film.”

“Has Bergman begun to make Bergman films? I find that Autumn Sonata is an annoying example.”

“Had I had the strength to do what I intended at the beginning, it would not have turned out that way.”

On the results Bergman states the following:

“It is impossible to discern how a film evolved and why it ended up as it did.”

“Why did I choose this story, and why was it so complete? It was more finished in the outline than the execution.”

“The daughter finally gives birth to the mother. Through this reversal they unite for a few brief moments in perfect symbiosis.”

“The idea that Helena gives birth to her mother is a difficult one to convey and one which, I’m sad to say, I abandoned.”

In that quartet of statements we see the struggle of creation. It is a bit of a wonder that Bergman simultaneously complains of the film being too Bergman but complains of this inability to create a symbiosis of character in this film. A symbiosis which would undoubtedly cause instant comparison to Persona.

In one way it reminds me on the latter chapters of Hitchcock’s Notebooks where later in his career Hitch seemed to be getting overwrought and unable to clearly to convey to his leads who the characters were. Here the result is clearly one of superior quality, and one of the Best in Bergman’s career in my estimation, but the statement does represent a kind of disconnect. Had he attempted and succeeded in having the daughter birth the mother it would’ve been even more Bergman than the French critic initially cited, yet somehow more successful. Certainly it points to that uncertainty in his feeling that it had failed for unknown reasons.

Ingmar made it clear he felt he hung Liv out to try in order to better manage Ingrid. I don’t necessarily agree with these statements but here were his impressions:

“I was difficult to work with these two actresses together. When I look at the film today, I see that I left Liv to shift for herself when I ought to have been more supportive.”

“In a few scenes she sometimes goes astray”

What made Ingmar need to dedicate so much additional attention to Ingrid. His own words on the matter are as follows:

“The idea was rekindled when “at the screening of Cries and Whispers she had snuck a note in my pocket which she reminded me of my promise that we would work together.” One of the things they first discussed was bringing “Hjalmar Bergman’s novel The Boss, Mrs. Ingeborg to film.”

The ideal to Bergman: “Three acts in three kinds of lighting: One evening light, one night light, and one morning light. No cumbersome sets, two farces, and three kinds of lighting.

“Therein lies an emotion that I was not able to realize and carry through to its conclusion.” “That is an unerring symptom of creative exhaustion, exceedingly dangerous because it doesn’t hurt.”

Autumn Sonata developed as it did and Ingmar said of Ingrid: “I did not have what one would call difficulties in my working relationship with Ingrid Bergman” but a “kind of a language barrier, but in a profound sense.” Meaning that after the table read, and through the first few days of production he “Discovered that she had rehearsed her entire part in front of the mirror, complete with intonations and self-conscious gestures.” The language barrier comment makes more sense as you continue to read “It was clear that she had a different approach to her profession han the rest of us. She was still living in the 1940s” and had “Different approach due to generational acting style preference.” While it didn’t click with Bergman he didn’t discount it entirely calling it an “inspired system of working, albeit a strange one.”

Late in the writing he pondered her prior working habits. “She still must have been somehow receptive to suggestions from two or three of her former directors.” “In Hitchcock’s films, for instance, she is always magnificent. She detested the man.” Of Hitchcock Bergman said:

“I believe that with her he never hesitated to be disrespectful and arrogant, which evidently was precisely the best method to make her listen.”

This lead to Bergman feeling that he “was forced to use tactics I normally rejected, the first and foremost being aggression.”

Later in interviews shed some light on the on-set relationship saying Ingmar confronted Ingrid. When he showed her dailies at her request. She was in agreement about her dated, inaccurate approach to the film, she asked for and got reshoots and things were somewhat better from there. However, considering all these facts Ingrid saying “‘If you don’t tell me how you want me to do in this scene, I’ll slap you!’” makes more sense. He wanted to work with actors to interpret text interestingly not dictate. It is a funny and insightful line because most directors at some point wish they could hear that exact thing rather than being fearful of stepping on toes.

Still he said that Ingrid was ultimately “generous, grand, and highly talented.” And was made aware that she was fighting cancer after their first on-set heart-to-heart where they reached a somewhat better understanding of one another.

It is really interesting that this collaboration occurred. However, based on her track record of seeking Hollywood on her own terms, contacting Rossellini and wanting to work with him, and then dropping Bergman a note; it seems she liked a challenge and to be a bit uncomfortable, as each of these stages of her career brought her much different environments and working conditions than she was heretofore used to.

The fact of the matter is that Brando and Dean brought actors to the fore anew as creators. This was after Ingrid made a name for herself, and while she challenged herself with new directors she did not evolve but rather refined her own method, so it’s natural that there was some friction.

Autumn Sonata by Ingmar Bergman

After having prepared the aforementioned notes the next thing I wanted to do was to read the screenplay anew. This would mark a third reading for me. All from a photocopy I ran off of a paperback I happened to find.

The script runs for a total of 21 scenes on 83 pages. The first is labeled as a Prologue. The added characters which are embodied and speaking are Viktor (Erland Josephson), a parson, representative of his father, based on his biography and other films and Helena (Lena Nyman).

Some of the themes touched upon are rather familiar such as the cultural references, the existential themes, a dead child, the topic of abortion; discussions of childishness and the nature of adulthood, travel, culinarian are a bit unique to the proceedings but not unlike how Bergman handles subjects. It’s also further interesting in hindsight to note that struggling with adulthood is not just for Millennials, and it never has been.

As for Bergman doing Bergman, it occurred to me while reading that many of his motifs are there but in many ways better than they were ever realized. In some ways its reminiscent on my thoughts on Madonna’s MDNA album, which were that it reminded me of everything she ever did but was wholly new.

As opposed to Ibsen’s Ghosts who were the central characters, the ghosts here a literal literary ones and are characters mentioned in passing or musicians. Examples include, but are not limited to; Agnes, Leonardo, Paul, Schneiderhahn, Starker, Janos, Nurse, Master Harold, Samuel Parkenhurst, Varvisio, Chopin, Adam Kretzinsky, Maria van Eyck, Father, Schmeiss, Stefan, Grandmother, Grandpa, Paul.

Some dialogue changes are lamentable, like the wonderful image of “Cloudberries on the Bog” being lost but ultimately Bergman was the end arbiter of his script on film, and likely the closest thing to a cinematic playwright as we ever so. Therefore, I typically trust his judgment.

The script is a testament to how the visual dictates the focus of the narrative, simply by its omission in the text most of the time. You are given the images you need in the end product. Furthermore, the reveal of one of the characters (Helena) being present is itself a plot point underscoring that the script is character driven as characters literally are the plot.

It’s a document that allows the actors to play subtextually, and is even contains metatextual moments with Viktor describing his wife to the audience. Furthermore, it allows characters soliloquies a technique usually reserved for the stage.

Eva’s soliloquy on Erik’s drowning. She then speaks of him as a near- literal ghost, talked about intriguingly as present. This allows her to transition to religion. Bergman was always described as one seeking to creat a map of the soul, and going into this realm and everywhere in between is why. It’s also interesting that in this story there is more faith found in Eva than in the parson.

It paints Charlotte as a woman who relates all things to music because reality is hard, and getting outside her own head and life is even harder. She has spent years seeking the secrets of the preludes, but those of life elude her and do not demand nearly as much of her attention. She practices an art of interpreting others as a means to express oneself. But her dedication to, and ability to mother has always been suspect at best.

There are passive-aggressive moments and the heights and depths of volume with persistent intensity. All indicated through the dialogue and rarely with parenthetical directions,

In technical terms the first lengthy parenthetical action/discription on Page 43. Now based on what I’ve seen Bergman’s scripts are a bit unorthodox anyway, especially as compared to standard Hollywood formatting. Sometimes you’ll see scripts dumbed down to an easier to read interface similar to stage plays. There usually is no indication of the visuals or the blocking. Bergman knew these things but divulged them when the time came. The screenplay is and has been an ever-evolving blueprint for a film and Bergman had his own way of fashioning his.

The ending of the script is insistent and offers a glimmer of hope. However, clearly can be no facile reconciliation. Nor may there be one at all. All endings besides the one offered would be false. It is a tale wherein mother and daughter have become estranged and the daughter still holds on the adolescent tendency to blame one’s parents for all their faults, and a mother who shares a certain burden of guilt never having felt entirely at ease in her role at home.

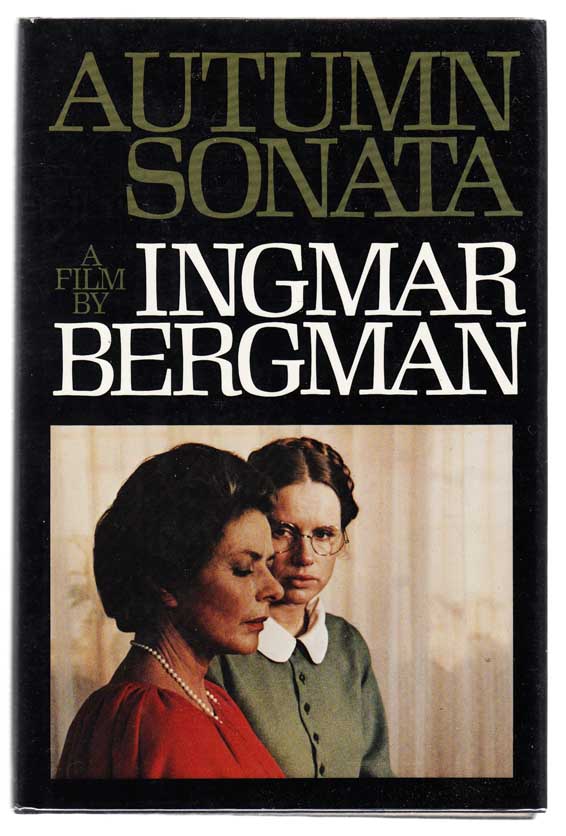

Autumn Sonata (1978)

As mentioned above the cast members in flashback nor some of the visuals are mentioned in the script. Most notably a photo of Erik, a photo of Leonardo Charlotte delivers a soliloquy to, and a scene where slides are being projected.

Bergman/Nyqvist’s affinity for using mirrors and reflections also shows up in the end product; as well as the emphasis on having the camera on the person listening at times for an extended period, of having both framed is brilliant, and allows Ingrid Bergman to shine and carry the film every bit as much when she’s listening as she does when speaking.

Clearly the indication of the emotions that will be conveyed by the disparate playing of the sonatas can’t really come across in the script, and Bergman did fake it very well indeed, as she claimed she could. Both list to one another play captivatingly.

This is as good a time as any to mention that there is a brilliant three-and-a-half hour documentary on the making of the film. While watching the process is fascinating there is only so much that can be gleaned, a bit of it will be indicated later. But some changes are never examined like the fact that Ingrid rehearsed phone calls to her agent in Swedish and then in the film they were in English. It was a great touch but that was one change I was looking forward to seeing happen.

In visual terms, the success of Autumn Sonata at the end truly hinges in Ingrid Bergman’s expression as Charlotte is seen reacting to Eva’s letter. The pain is clear, and if there is any reconciliation even possible is left nebulous at best.

Ingrid Bergman Interview at NFT

In a revealing interview at the National Film Theatre in London Ingrid sat down to discuss her career, and her at that time most recent film, Autumn Sonata. She touched on her desire to change, as evidenced by the phases of her career. The fact that she was independent was something that contrarian, and likely contributed to her gaining fans and losing them when she was turned on during the height of the Red Scare, and she stayed off the American screen until she made Anastasia.

This maverick streak was there from the start as she played under only one contract during her whole career, a four-year one with David O. Selznick following the success of Intermezzo. She was always a freelancer after that, which made her shift to working in the Italian cinema with Rossellini easier to accomplish logistically.

Bergman’s involvement with Rossellini professionally and personally made him possessive and she was not allowed to work with anyone else when they were together until Jean Renoir spoke to him. Owing to Rosselini’s respect for Renoir he allowed the two to collaborate.

When speaking of Bergman she talked of how they got to know one another, and how he joked that they were “brother and sister.” She spoke of her determination to work with him that it was “written in fire over my forehead.” Considering she wrote Rossellini out of the blue it was sure to happen even though it was a project that faced many delays.

As an actress who had worked in German, English, French, and Italian in the years since her last Swedish film (in her homeland) she stated it wasn’t hard to get back into and it was a “great relief after so many years. I can’t believe it was so easy to learn the dialogue.”

As an actress who learned English to play her first American role, it should surprise no one that she had piano instruction again for the first time since she was 13 to be able to convincingly fake her piano playing for Autumn Sonata.

With regards to the film she felt quite a bit of connection. Saying that a lot of it was her life, leaving her home and her children, be it for work or relationships dissolving. “That just makes me very sad because I’ve done it many times,” she stated.

She also admitted to arguing with Ingmar over certain points but didn’t frame these stories with bias. She thought certain lines and facts of the story were hard to swallow, complaining that the time Charlotte and Eva spent apart was “inhuman.” Bergman usually won out stating “We’re not telling your story it’s Charlotte’s.”

Interview with Bergman

This feature includes the full (and I believe unedited) interview footage with Bergman on Farö Island which was filmed for the documentary Bergman Island.

Here Bergman again related much of the story, with no major details changing, just more information. Much of which Ullmann corroborates at a later date.

Bergman discusses having a fear headache based on the performance he believed he was getting. He was finding he couldn’t direct her. When they sat and talked he found out about Ingrid’s cancer, she took the notes well and professionally, and in hoping to merely reach a sort of compromise he saw she agreed and came around.

He felt at that point her sensitivities opened up to the truer nature of the character. My feeling is her defensiveness my have been built up due in part to her health issues, a hiatus from work, and dealing with a new director with a different vision. Maybe the tendency to lean on old habits proved too strong. Thankfully for her, Ingmar, and the film she came through it.

Interview with Liv Ullmann

Having recently read a book of her interviews I was wondering what Liv could offer her. Being a newer interview, and after the deaths of both Ingmar and Ingrid added an emotional tenor to the matter but also some new information.

The first aspect of which was that she really was in on the ground floor. As parents together, former lover, and now collaborator, Ullmann knew this project existed before Bergman realized this was the perfect vehicle for Ingrid. The realization that it had to be her came a bit later.

Ullmann, as could be expected, gives great insight into the script and characters by her and Ingrid; two fiercely independent women. They both identified with playing women who needed to give of her own creativity, and could relate to the fact that society would tell them they could not do so. While I understand their quibbles with how audiences may interpret these characters, I believe that not every character is not a referendum on a gender or a race or group.

She learned in this film how vulnerable emotionally a director who writes is, and she didn’t really appreciate it then. Ingmar was unused to this questioning, and was one to not allow changes in wording. She doesn’t feel Ingmar and Ingrid ever real communication that they creating from themselves.

In Ingmar’s defense Liv does state she doesn’t like too many questions being asked, nor the director telling her too much. Her ability to create on her own, and play against dialogue allowed her the freedom to make Autumn Sonata work as well as it does.

Ullmann related how Bergman had a tradition of screening a film of his choosing for all cast and crew on Wednesday night. One day Ingrid had had enough, and was tired and left five minutes in. It was something that wasn’t done. Liv envied that but would never dream of doing so herself.

Liv credited Ingrid for in the end she never actually said no. She questioned things but eventually did do as she was asked. Perhaps the prime example of that is the fact that Ingrid wanted to slap Eva for what she was saying to her mother and it caused a big fight on set. Eventually she performed the scene as scripted. Liv was astounded at the results that through her choked back tears and rage she expressed “the anger of every woman who was forced to apologize” for choosing to create and have a family. The subtextual truth comes out.

What I came away with from the interview is that subtext wins over time, and the commentary is made without dialogue but through these actions and interactions.

Conclusion: The Booklet

The Criterion Collection’s final nugget of wisdom on this film is the booklet (and bless them for still making them) is Farran Smith Nehme’s insightful essay on the film.

She rightly underscores that not only does the film scratch something off Ingrid’s proverbial bucket list, but it’s also Bergman’s final film created expressly for cinema. All his films afterward usually debuted on TV and then went to cinemas in either edited or unedited forms.

While its “built on exposition” and not metaphysical it still is Bergman with its touches and I think it’s an essay that helps frame the brilliance and surreal nature of having Ingrid Bergman in an Ingmar Bergman film one that feels not only intensely personal to those involved. Whether or not these fine actresses were allowed to say what they wanted to say about their own lives they expressed truths that could connect to all on either side of the parent-child relationship. As flawed, improbable, monstrous or sympathetic you find these figures they are written and played by wonderous artists that allow you to identify with them regardless of the facts of their case. It’s compelling to watch, and one thing Bergman was inarguably right about is that it had to be Liv and Ingrid. No question about it.